- Home

- Walt Whitman

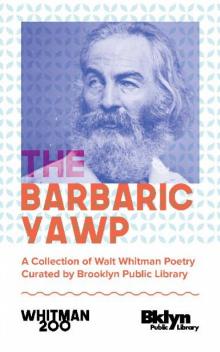

The Barbaric Yawp

The Barbaric Yawp Read online

The Barbaric Yawp: A Collection of Walt Whitman Poetry Curated by Brooklyn Public Library

Published in 2019 by Brooklyn Public Library for Whitman 200, a celebration of Walt Whitman’s 200th birthday.

All poems were written by Walt Whitman and are in the public domain.

All photographs are part of the Brooklyn Collection at Brooklyn Public Library. Copyright restrictions apply.

Brooklyn Public Library

bklynlibrary.org

Table of Contents

Introduction Crossing Brooklyn Ferry

I Sing the Body Electric

Poem of Faces

I am He that Aches with Love

City of Orgies

The Sleepers

To a Stranger

On the Beach at Night

As if a Phantom Caress’d Me

As I Ebb’d with the Ocean of Life

The Dalliance of the Eagles

When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d

Song of Myself (1892 version)

Introduction

2019 marks the 200th birthday of Walt Whitman, America’s literary radical and great poet of democracy. His slim, self-published (and largely self-designed, typeset, and distributed) 12 poem Leaves of Grass was printed in Brooklyn on July 4th 1855 out of a small shop owned by the Rome brothers on Fulton and Cranberry streets. The first edition of Leaves of Grass listed no author name on its title page. Instead, on its frontispiece was included a portrait of its swarthy creator - hat cocked to one side, one hand in a pocket, the other on his hip, slouchy, bearded, dressed in a working man’s clothes with shirt collar widely unbuttoned and eyes staring straight ahead as if daring the reader to engage.

And though it still vibrates with a revolutionary energy well over a century and a half after its inaugural edition, the few first readers of Leaves of Grass largely dismissed it as the product of a disturbed mind. The handful of reviews it received declared it vulgar, disjointed, sinful, and pretentious. The Saturday Review recommended burning the book. Calvin Beach, after admitting to having scanned just a few lines, was so personally offended by what he read that he suggested in The New York Saturday Press that Whitman should commit suicide by throwing himself off a cliff into the ocean. A slightly softer, if no less damning take, from the Dublin Review cast the unusual collection of poems as “a farrago of rubbish,—lucubrations more like the ravings of a drunkard, or one half crazy, than anything which a man in his senses could think it fit to offer to the consideration of his fellow men.” One can readily imagine a frustrated mid-19th century reviewer paging back to Whitman’s frontispiece portrait after reading lines like “Loveflesh swelling and deliciously aching, Limitless limpid jets of love hot and enormous” to look into the confident, daring eyes of the 37 year-old poet to wonder, What on earth were you thinking?

Whitman’s poetic universe contained everything and everyone, he plucked subjects from his own time and, more ambitiously, from all times before and after. He wrote about the opera and ship building, freckles and beards, benevolent societies and the soul, farmers and the odor of hair, Brooklyn and Mannahatta, suicide and the heat and electricity of city crowds, the “Goods of guttapercha or papiermache” and sex. Quite a bit of sex. Whitman collapsed the distance between high culture and the unsung daily rituals of the masses; declared equally beautiful the ancient mystery of the limitless soul and the ineluctable fact of our corporeal yearnings, expulsions, and decay. To Whitman, all of it was magnificent. Contained in all things, at all times, are the faint murmurings of whatever ancient spirit nudged this world into being - and the poet’s job is to be curious, to listen, and to write it all down.

In the year of his 200th birthday, I wonder how Walt Whitman would use our libraries if he were alive today. He’d no doubt be one of our most frequent, and vocal members. He’d know the names of every librarian, custodian, literacy instructor, and volunteer in this place. And I’d likely get a few calls and emails regarding this curious Brooklynite.

He’d stroll through our stacks – checking out armloads of books, hanging around the reference desk peppering our librarians with oddball questions, asking for book recommendations (and no doubt offering some of his own), sharing with strangers sudden musings on phrenology or mycology or swim bladders or metempsychosis, launching unprovoked into recitation of Shakespeare soliloquies, volunteering to lead a conversation group for new Americans, getting lost in our Brooklyn Daily Eagle Archive, recording a podcast in our studio, donating books to our jail libraries, soap boxing and arguing into the small hours of the morning at our annual Night of Philosophy, taking a social media class to learn how to Tweet at Oscar Wilde, spending hours with our musical score collection, being one of the first people at the door waiting for us to open in the morning, and one of the last to leave at night. Walt would be one of our favorites. He’d urge us to be better. He’d demonstrate empathy, curiosity, unflagging commitment to intellectual freedom, and he would demand that we do the same. This place of debate and critical thinking, of research and culture, of inclusive community and radical empathy - our public libraries were made for Walt Whitman.

The truth is Walt is already strolling through our stacks. I see Walt in so many of our library patrons. I see him in our omnivorous readers and his spirit is in the curious strangeness of some of our reference questions. He emerges in the research of the autodidacts and shares a seat among adults learning to read. A few Whitmans have joined our 1984 book club, and Whitman surely volunteers in our Books by Mail service for homebound seniors. I encounter the curiosity, empathy, love and wisdom of Whitman in our library staff. And for the poet who spent a great deal of his adult life caring for others (particularly wounded soldiers during and after the American Civil War), he would have found great affinity of spirit in an institution and profession whose currency is empathy, and one of its guiding principles, inclusion.

The poems collected in this commemorative Walt Whitman e-book were specially chosen by Brooklyn librarians and archivists. The accompanying photographs were similarly curated and sourced from our Brooklyn Collection archive. These are some of our favorite Whitman poems, and we hope you enjoy them as much as we do. We envision these poems being pulled up on one’s phone or other device while traveling across the city, or sitting in the park, or waiting in line for a bagel. We hope this makes it easier to handily carry the universe in your coat pocket and, as Walt recommends, “to read these leaves in the open air every season of every year of your life.”

Nick Higgins

Chief Librarian, Brooklyn Public Library

Lower Manhattan from Ferry, 1893

Edgar S. Thomson photograph collection, Brooklyn Museum/Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection

Crossing Brooklyn Ferry

1

Flood-tide below me! I see you face to face!

Clouds of the west—sun there half an hour high—I see you also face to face.

Crowds of men and women attired in the usual costumes, how curious you are to me!

On the ferry-boats the hundreds and hundreds that cross, returning home, are more curious to me than you suppose,

And you that shall cross from shore to shore years hence are more to me, and more in my meditations, than you might suppose.

2

The impalpable sustenance of me from all things at all hours of the day,

The simple, compact, well-join’d scheme, myself disintegrated, every one disintegrated yet part of the scheme,

The similitudes of the past and those of the future,

The glories strung like beads on my smallest sights and hearings, on the walk in the street and the passage over the river,

The current rushing so swiftly and swimming with me far away,

/>

The others that are to follow me, the ties between me and them,

The certainty of others, the life, love, sight, hearing of others.

Others will enter the gates of the ferry and cross from shore to shore,

Others will watch the run of the flood-tide,

Others will see the shipping of Manhattan north and west, and the heights of Brooklyn to the south and east,

Others will see the islands large and small;

Fifty years hence, others will see them as they cross, the sun half an hour high,

A hundred years hence, or ever so many hundred years hence, others will see them,

Will enjoy the sunset, the pouring-in of the flood-tide, the falling-back to the sea of the ebb-tide.

3

It avails not, time nor place—distance avails not,

I am with you, you men and women of a generation, or ever so many generations hence,

Just as you feel when you look on the river and sky, so I felt,

Just as any of you is one of a living crowd, I was one of a crowd,

Just as you are refresh’d by the gladness of the river and the bright flow, I was refresh’d,

Just as you stand and lean on the rail, yet hurry with the swift current, I stood yet was hurried,

Just as you look on the numberless masts of ships and the thick-stemm’d pipes of steamboats, I look’d.

I too many and many a time cross’d the river of old,

Watched the Twelfth-month sea-gulls, saw them high in the air floating with motionless wings, oscillating their bodies,

Saw how the glistening yellow lit up parts of their bodies and left the rest in strong shadow,

Saw the slow-wheeling circles and the gradual edging toward the south,

Saw the reflection of the summer sky in the water,

Had my eyes dazzled by the shimmering track of beams,

Look’d at the fine centrifugal spokes of light round the shape of my head in the sunlit water,

Look’d on the haze on the hills southward and south-westward,

Look’d on the vapor as it flew in fleeces tinged with violet,

Look’d toward the lower bay to notice the vessels arriving,

Saw their approach, saw aboard those that were near me,

Saw the white sails of schooners and sloops, saw the ships at anchor,

The sailors at work in the rigging or out astride the spars,

The round masts, the swinging motion of the hulls, the slender serpentine pennants,

The large and small steamers in motion, the pilots in their pilot-houses,

The white wake left by the passage, the quick tremulous whirl of the wheels,

The flags of all nations, the falling of them at sunset,

The scallop-edged waves in the twilight, the ladled cups, the frolicsome crests and glistening,

The stretch afar growing dimmer and dimmer, the gray walls of the granite storehouses by the docks,

On the river the shadowy group, the big steam-tug closely flank’d on each side by the barges, the hay-boat, the belated lighter,

On the neighboring shore the fires from the foundry chimneys burning high and glaringly into the night,

Casting their flicker of black contrasted with wild red and yellow light over the tops of houses, and down into the clefts of streets.

4

These and all else were to me the same as they are to you,

I loved well those cities, loved well the stately and rapid river,

The men and women I saw were all near to me,

Others the same—others who look back on me because I look’d forward to them,

(The time will come, though I stop here to-day and to-night.)

5

What is it then between us?

What is the count of the scores or hundreds of years between us?

Whatever it is, it avails not—distance avails not, and place avails not,

I too lived, Brooklyn of ample hills was mine,

I too walk’d the streets of Manhattan island, and bathed in the waters around it,

I too felt the curious abrupt questionings stir within me,

In the day among crowds of people sometimes they came upon me,

In my walks home late at night or as I lay in my bed they came upon me,

I too had been struck from the float forever held in solution,

I too had receiv’d identity by my body,

That I was I knew was of my body, and what I should be I knew I should be of my body.

6

It is not upon you alone the dark patches fall,

The dark threw its patches down upon me also,

The best I had done seem’d to me blank and suspicious,

My great thoughts as I supposed them, were they not in reality meagre?

Nor is it you alone who know what it is to be evil,

I am he who knew what it was to be evil,

I too knitted the old knot of contrariety,

Blabb’d, blush’d, resented, lied, stole, grudg’d,

Had guile, anger, lust, hot wishes I dared not speak,

Was wayward, vain, greedy, shallow, sly, cowardly, malignant,

The wolf, the snake, the hog, not wanting in me,

The cheating look, the frivolous word, the adulterous wish, not wanting,

Refusals, hates, postponements, meanness, laziness, none of these wanting,

Was one with the rest, the days and haps of the rest,

Was call’d by my nighest name by clear loud voices of young men as they saw me approaching or passing,

Felt their arms on my neck as I stood, or the negligent leaning of their flesh against me as I sat,

Saw many I loved in the street or ferry-boat or public assembly, yet never told them a word,

Lived the same life with the rest, the same old laughing, gnawing, sleeping,

Play’d the part that still looks back on the actor or actress,

The same old role, the role that is what we make it, as great as we like,

Or as small as we like, or both great and small.

7

Closer yet I approach you,

What thought you have of me now, I had as much of you—I laid in my stores in advance,

I consider’d long and seriously of you before you were born.

Who was to know what should come home to me?

Who knows but I am enjoying this?

Who knows, for all the distance, but I am as good as looking at you now, for all you cannot see me?

8

Ah, what can ever be more stately and admirable to me than mast-hemm’d Manhattan?

River and sunset and scallop-edg’d waves of flood-tide?

The sea-gulls oscillating their bodies, the hay-boat in the twilight, and the belated lighter?

What gods can exceed these that clasp me by the hand, and with voices I love call me promptly and loudly by my nighest name as I approach?

What is more subtle than this which ties me to the woman or man that looks in my face?

Which fuses me into you now, and pours my meaning into you?

We understand then do we not?

What I promis’d without mentioning it, have you not accepted?

What the study could not teach—what the preaching could not accomplish is accomplish’d, is it not?

9

Flow on, river! flow with the flood-tide, and ebb with the ebb-tide!

Frolic on, crested and scallop-edg’d waves!

Gorgeous clouds of the sunset! drench with your splendor me, or the men and women generations after me!

Cross from shore to shore, countless crowds of passengers!

Stand up, tall masts of Mannahatta! stand up, beautiful hills of Brooklyn!

Throb, baffled and curious brain! throw out questions and answers!

Suspend here and everywhere, eternal float of solution!

Gaze, loving and thirsting eyes, in the house or street or public assembly!

Sound out, voices of young men! loudly and musically call me by my nighest name!

Live, old life! play the part that looks back on the actor or actress!

Play the old role, the role that is great or small according as one makes it!

Consider, you who peruse me, whether I may not in unknown ways be looking upon you;

Be firm, rail over the river, to support those who lean idly, yet haste with the hasting current;

Fly on, sea-birds! fly sideways, or wheel in large circles high in the air;

Receive the summer sky, you water, and faithfully hold it till all downcast eyes have time to take it from you!

Diverge, fine spokes of light, from the shape of my head, or any one’s head, in the sunlit water!

Come on, ships from the lower bay! pass up or down, white-sail’d schooners, sloops, lighters!

Flaunt away, flags of all nations! be duly lower’d at sunset!

Burn high your fires, foundry chimneys! cast black shadows at nightfall! cast red and yellow light over the tops of the houses!

Appearances, now or henceforth, indicate what you are,

You necessary film, continue to envelop the soul,

About my body for me, and your body for you, be hung out divinest aromas,

Thrive, cities—bring your freight, bring your shows, ample and sufficient rivers,

Expand, being than which none else is perhaps more spiritual,

Leaves of Grass: First and Death-Bed Editions

Leaves of Grass: First and Death-Bed Editions Alone on the Beach at Night

Alone on the Beach at Night The Barbaric Yawp

The Barbaric Yawp The Walt Whitman MEGAPACK

The Walt Whitman MEGAPACK Drum-Taps: The Complete 1865 Edition

Drum-Taps: The Complete 1865 Edition Specimen Days & Collect

Specimen Days & Collect On the Beach at Night Alone

On the Beach at Night Alone Drum-Taps

Drum-Taps